When it comes to privacy and accountability, people always demand the former for themselves and the latter for everyone else.

– David Brin, American author

Since one twin was ordered by court to give handwriting samples after being arrested for using stolen credit card, the other twin’s appearing and giving the handwriting samples was designed to prevent his brother from so doing and amounted to obstruction of justice.

– Elliott v. U.S., 385 A.2d 183 (D.C. 1978).

The Future of Shopping

There is no question that “big data” plays a big role in how retailers will market and engage with customers. As technology, social media, and the shopping experience continues to evolve, you will find retailers spending big money on data control and management. A great example is found in the recent article “Retailers are going to get very personal in 2039” by Cadie Thompson at CNBC.

Hey, That’s Personal!

What’s more personal than one’s own identity? I think the key to answering such a question turns on how you define “identity” in such a question. Sure, a person’s name and address, both clearly personal identifiers of an individual person, nevertheless is public information as it sits in the phone book and, in more modern terms, in online databases.

However, add an additional, non-public identifier, such as a social security number, driver’s license number, financial institution account number, or debit/credit card number, and the layers of identity quickly get peeled back.

Personal Information in the Retail Arena

Just 20 (or so) years ago, I can remember checking my college grades posted on hallway walls not by name (because that would be too personal, ha), but by the long laundry lists of each person’s social security number (ahhh, much safer!). While those times of seem to have changed, the risks of leaked, lost, and stolen personal information (read: identity theft) continue to grow and change in form and method.

How many times have you been asked for a telephone number in the checkout line? (Do you give them your office number too? Or a fake one? Or simply refuse?) How about your ZIP code? – “Oh, it’s just for our internal stats,” the clerk may tell you, as your ever suspicious attitude is not diminished.

Why would a retailer, or any commercial entity for that matter, WANT to gather so much personal information about you? Isn’t that putting THEM at risk if (when) others get it and use it for evil means? Well, the likely answer is that the financial gains from uses of that information outweigh the risks, or so they think. Retailers acquire the personal information for their own business purposes—for example, to build mailing and telephone lists—which they can subsequently use for their own in-house marketing efforts or sell to direct-mail or tele-marketing specialists, and so on.

The Government Will Protect Me, Right?

A landmark case in this area of the law was the 2011 California Supreme Court case of Pineda v. Williams-Sonoma Stores, Inc., 51 Cal.4th 524, 120 Cal.Rptr.3d 531, 246 P.3d 612 (Cal., 2011). The plaintiff made a purchase at defendant’s store in San Diego County with her credit card when the clerk requested her ZIP code as part of the transaction. Under the belief that it was required to provide her ZIP to complete the sale, she supplied it, giving the retailer her credit card number, name on her card, and ZIP code. Problem?

The California Supreme Court, in interpreting the state’s Song-Beverly Credit Card Act of 1971 (CA Civ.Code, § 1747 et seq.), concluded that ONLY the ZIP code without her entire address would constitute “facially individualized information” as to violate California law. The Act prohibits businesses from requesting that cardholders provide “personal identification information” during credit card transactions, and then recording that information. (CA Civ.Code, 1747.08(a)(2)).

The California Supreme Court pointed out:

- A ZIP code is readily understood to be part of an address; when one addresses a letter to another person, a ZIP code is always included. Thus, a ZIP code alone must be “personal identification information” otherwise a business could ask not just for a cardholder’s ZIP code, but also for the cardholder’s street and city in addition to the ZIP code, so long as it did not also ask for the house number. Such a construction would render the statute’s protections hollow. Thus, the word “address” in the statute should be construed as encompassing not only a complete address, but also its components.

- A cardholder’s home address, for example, may pertain to a group of individuals living in the same household just as a single home telephone number may. The law explicitly provides that a cardholder’s address and telephone number constitute personal identification information, so the fact that such information might also pertain to individuals other than the cardholder is immaterial.

- Armed with the person’s name and ZIP code, unnecessary to the transaction, the company can locate his or her full address through reverse look-up.

Clearly this Court preferred a broader interpretation of the definition and legislative intent to protect personal identification, going as far as realizing that with a bite of information, entities may “reverse look-up” additional identifiers on a person to further populate a database.

Another even more recent example comes from Massachusetts in the case of Tyler v. Michaels Stores, Inc., 464 Mass. 492, 984 N.E.2d 737 (Mass., 2013). Employees of the defendant requested and recorded customers’ ZIP codes in processing credit card transactions in Massachusetts. Plaintiff, in a class action lawsuit, claimed this procedure was in violation of state law (Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 93, 105(a)) as a ZIP code constitutes personal identification information, regardless of a affirmative showing of any actual identity fraud.

According to the Court’s opinion, Michaels maintained a policy of writing customers’ names, credit card numbers, and ZIP codes on electronic credit card transaction forms in connection with credit card purchases. Michaels used Plaintiff’s name and ZIP code in conjunction with other commercially available databases to find her address and telephone number. Plaintiff subsequently received … wait for it… unsolicited and unwanted marketing material from Michaels.

In this case, the lower court dismissed the claim initially, arguing that the main purpose of state law is to prevent identity fraud and not to protect consumer privacy. The higher court reversed the dismissal and disagreed:

- The law’s intent is to limit disclosure of personal information leading to the identification of a particular consumer generally, and has no express purpose limited to identity theft.

- The law expressly “applies to all credit card transactions” and delineates a general prohibition that “[n]o person, firm, partnership, corporation or other business entity … shall write, cause to be written or require that a credit card holder write personal identification information, not required by the credit card issuer, on the credit card transaction form” (emphases supplied). The statute also defines “[p]ersonal identification information” in a nonexclusive manner, stating that the term “shall include, but shall not be limited to, a credit card holder’s address or telephone number.”

- Both the title (“CONSUMER PRIVACY IN COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS”) and caption of the state law expressly reference “consumer privacy in commercial transactions,” reinforcing the view that the legislature indeed was concerned, as Tyler suggests, about privacy issues in the realm of commercial dealings and in any event was not necessarily focused solely on preventing identity fraud.

- The law’s legislative history demonstrates its goal was to prohibit recording of personal information to prevent fraud and safeguard consumer privacy, and more particularly to protect consumers using credit cards from becoming the recipients of unwanted commercial solicitations from merchants.

Similarly, the Massachusetts Court found a consumer’s ZIP code does constitute “personal information” under its law as its use, when combined with the consumer’s name, provides the merchant with enough information to identify through publicly available databases the consumer’s address or telephone number, the very information the law expressly identifies as personal identification information, applying the very same logic as the California Supreme Court.

What About Scanning Driver’s License or State ID Cards?

Sure, many of us have given in to opening the door to much of our private lives with retailers through the use of their “loyalty cards” and similar programs. We often don’t want to miss out on saving a few dollars here and there, at the least, even though the commercial entity has voluntarily received not only our personal information (that form you filled out) but when, where, and how we buy what.

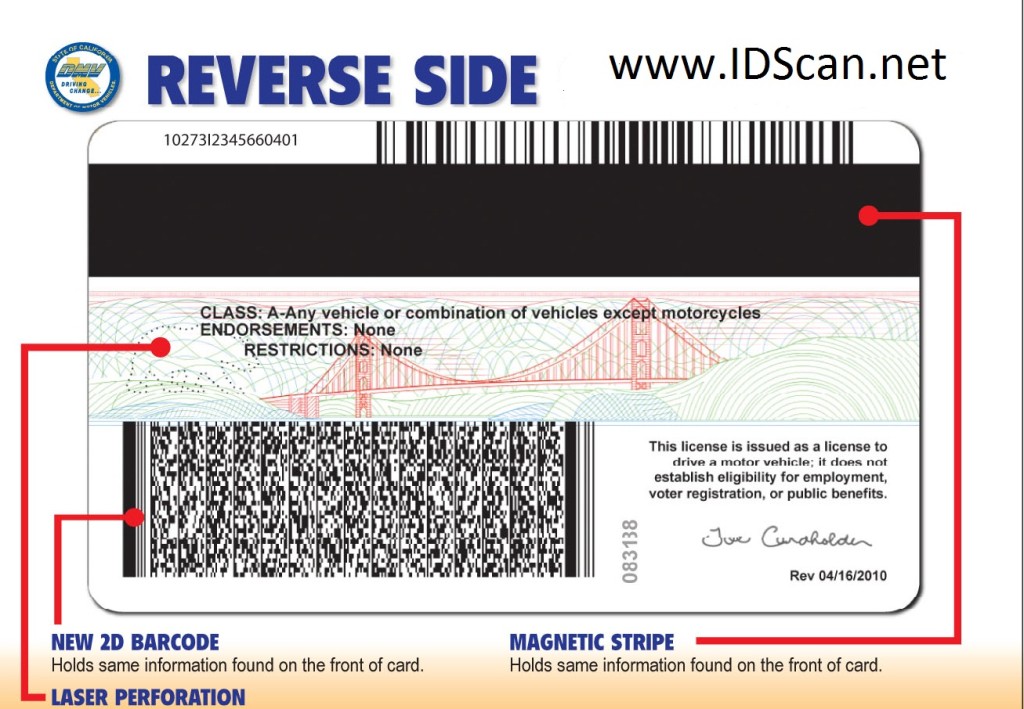

Ever purchase an “age restricted” item, e.g. cigarettes, alcohol, and have your ID not simply looked at by the clerk, but mechanically scanned in some manner (think: recorded)? Stores such as Target have said they only collect such information for use directly related to the transaction itself, i.e. just the date of birth. Some state-issued IDs, like my Illinois DL, contain a 2D barcode (typically a PDF417 style barcode) on the back that retailers are only supposed to be able to access the name, date of birth and drivers license number. Even if the retailer just has your Driver’s License number, it’s likely it can determine other information. Staying with my home state of Illinois, our DL number is determined by a soundex algorithm that is easily reverse engineered to learn your name, gender, and date of birth. (As a former police officer, I used this method every day to easily glace at a DL to compare the gender and DOB printed on the card with the coded DL number (without doing any complicated math) as a very good indication if it is a fake or altered ID.)

So, while proof of age (via an ID check) may certainly be legal, if not required by state law and/or local ordinance, may the retailer require a scan of an ID to complete a certain transaction such as confirming I am the authorized user of a credit card? – The answer likely turns on (1) what information is being collected and (2) what state laws or regulations may apply to restricting that commercial entity to collecting that specific information. Unfortunately, many times the consumer (and the retail clerk) do not know the answer to either.

There Are Always “Exceptions”

Although the Pineda and Tyler decisions should justifiably give retailers pause, there are legal justifications (i.e. exceptions) to many of these same laws. For example, the CA law does NOT apply to a list of situations such as entering your ZIP code at a self-serve gas pump, or when the information is required for shipping, delivery, servicing, or installation. Another exception is for confirming positive identification when accepting full or partial payment from a customer by credit card, “provided that none of the information contained thereon is written or recorded…” (CA Civil Code Section 1747.08(d)).

The Takeaway

Retailers continuing (or starting) to collect personal information from consumers in connection with credit card transactions should ensure they have a business need for the information, do so in the most restricted yet sufficient manner necessary, and comport with that jurisdiction’s laws and regs., including any required privacy notices of what is being collected and how it will be stored and used.

Better yet, they should sit down for a quiet and in-depth read of the Generally Accepted Privacy Principles adopted by The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants or the Federal Trade Commission‘s Fair Information Practice Principles.

Happy… and Safe… Shopping!

____

@travelblawg

facebook.com/travelblawg

Subscribe in the sidebar!

![]()

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission.

I think what’s challenging about this is that sometimes zip code is collected to process a transaction (i.e. AVS), and sometimes it’s being collected by the company so that they can do a reverse lookup and figure out exactly who you are. But yes, I no longer give out my zip code if I can help it!