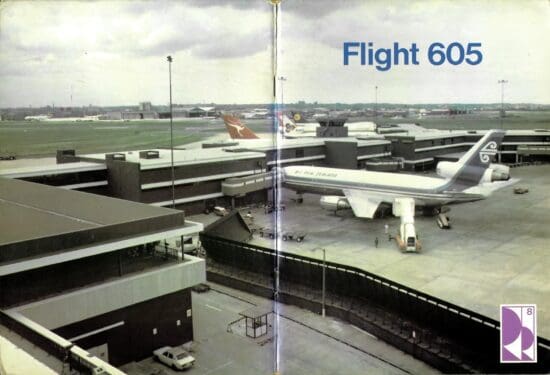

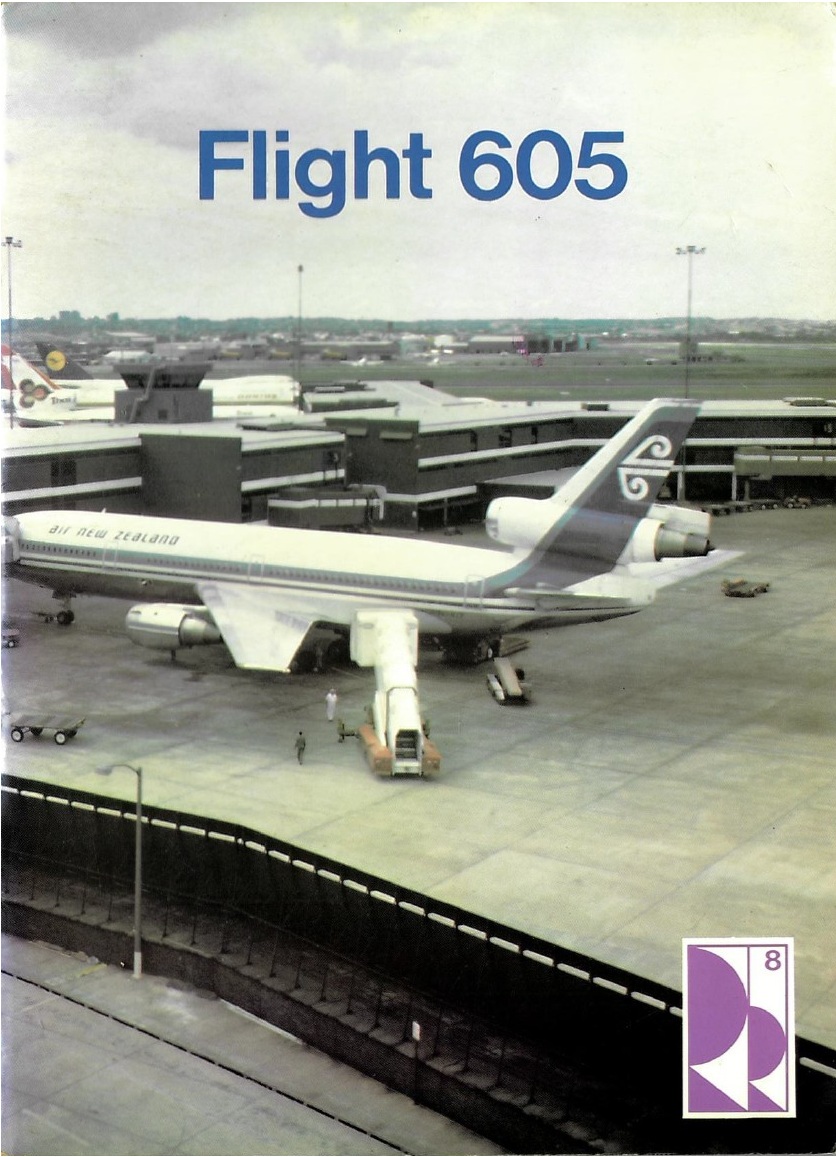

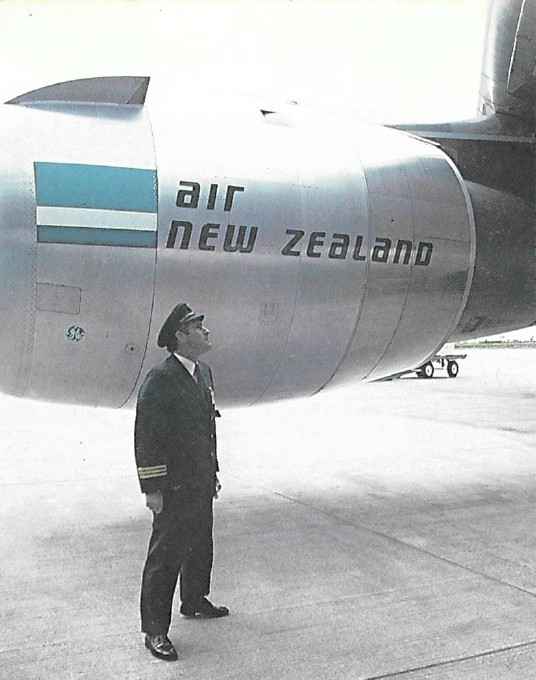

Back when I was in Primary School, there were a series of Reading Rigby books displayed at the front of the classroom. These are guided readers with books at various levels of complexity for children. One of them featured a picture of an Air New Zealand DC-10 on the cover and was called Flight 605.

According to the publication data, this book was first published in 1980 by Rigby Publishers. The text is copyright Gregory A Blaxell and Associates and Gordon Winch, with the images copyright Reading Rigby Pty Ltd. The ISBN is 0 7272 1136 7. But why am I telling you this?

Flight 605

It’s no secret that I have crazily into aviation since I was a kid. In our class, we didn’t use the Rigby Readers – I think they were mainly for the children learning English as a second language. That Flight 605 book looked at me for weeks until it came home with me. I still have it (sorry Ashbury Public School!).

At the Airport

I was told to be at the airport check-in at least an hour before the flight. This seemed a long time, but, after all, it was an international flight.

I arrived at the terminal and found the check-in desk. My flight was to Auckland, New Zealand. At the desk my suitcase was taken and I was given a customs and immigration form to fill in. Because there is a special arrangement between Australia and New Zealand, Australians and New Zealanders don’t need passports to travel between the two countries.

There was a short queue so all this took about ten minutes. Not very long after, the public address system announced, “Flight 605 is now ready for departure from gateway 3. Would all passengers complete customs and immigration and proceed to the boarding lounge? All aboard, please.”

While I’d been waiting for this boarding call, I’d heard similar announcements for other international flights. There was a Qantas flight to London, a Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt, and an Alitalia flight to Rome. For some of these flights the announcements were also made in German and Italian as well as English.

I went through the door into a room where several immigration officers were working. Each officer had a typewriter keyboard in front of him and a television display screen. These were connected to a computer. Each passenger leaving the country had to be checked by these men. I handed my completed customs and immigration form to an officer who checked it through the computer. Some of the other passengers needed a passport to travel on this flight, so this was checked too.

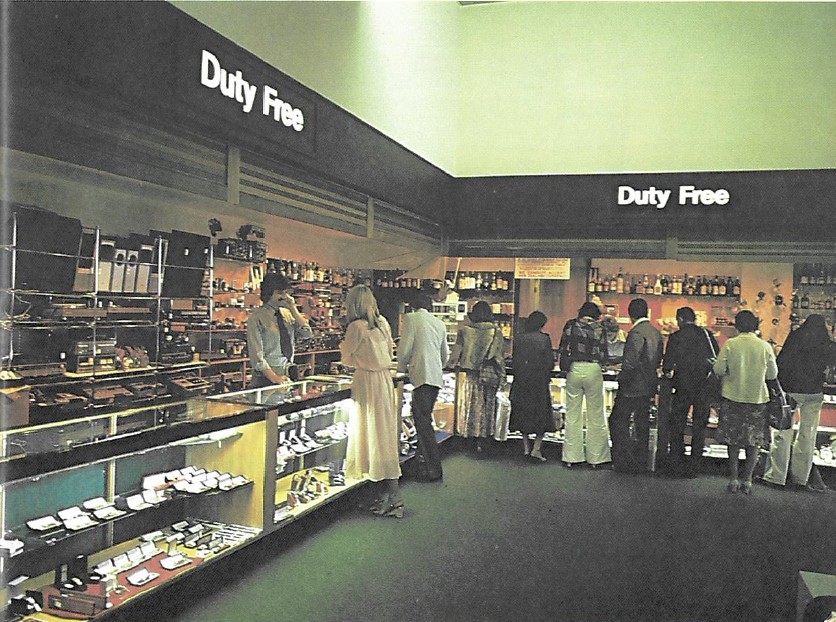

Once through the barrier, I walked along the concourse towards boarding gate 3. Several shops, called Duty Free Shops, were located here. Cameras, perfume, radios, watches, cigarettes, liquor and many other good can be bought at these shops much more cheaply than at normal stores.

There was only one more thing for me to do before I boarded the aircraft. Set up in the boarding lounge was a security checkpoint. The bag I was carrying was put through a machine and I was asked to walk through what looked like a door frame. The security check is to ensure that weapons or other dangerous things are not taken aboard the aircraft.

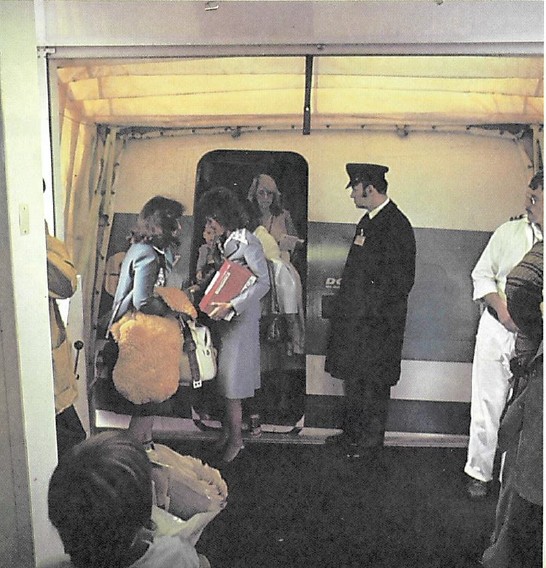

When all this was completed, the doors of the airbridge swung open and the passengers were asked to board. Tickets and boarding passes were checked by airline staff at the door to the airbridge and again at the door of the aircraft.

As the tractor pushed the aircraft away from the gate, I relaxed back into my seat. I knew that although I was relaxing and looking forward to my flight, many other people were very busy.

The Flight Crew

The Sydney-Auckland journey was the second part of the trip for the Air New Zealand crew. The aircraft had left Auckland at 9.30 a.m., Auckland time, and had arrived in Sydney three hours later. Because Auckland time is two hours ahead of Sydney, the time of arrival, Sydney time, was 10:30 a.m.

The Captain, First Officer and Flight Engineer had arrived at Auckland’s International Airport just after 8.15 a.m. They had been rostered to fly the Auckland-Sydney, Sydney-Auckland flight today. Last week the Captain had flown to Los Angeles, the First Officer had been to Hong Kong, but the Flight Engineer hadn’t flown at all.

As they were flying only for the day, they had driven their cars to the airport. At the end of the day they would drive home again; just like coming home from work.

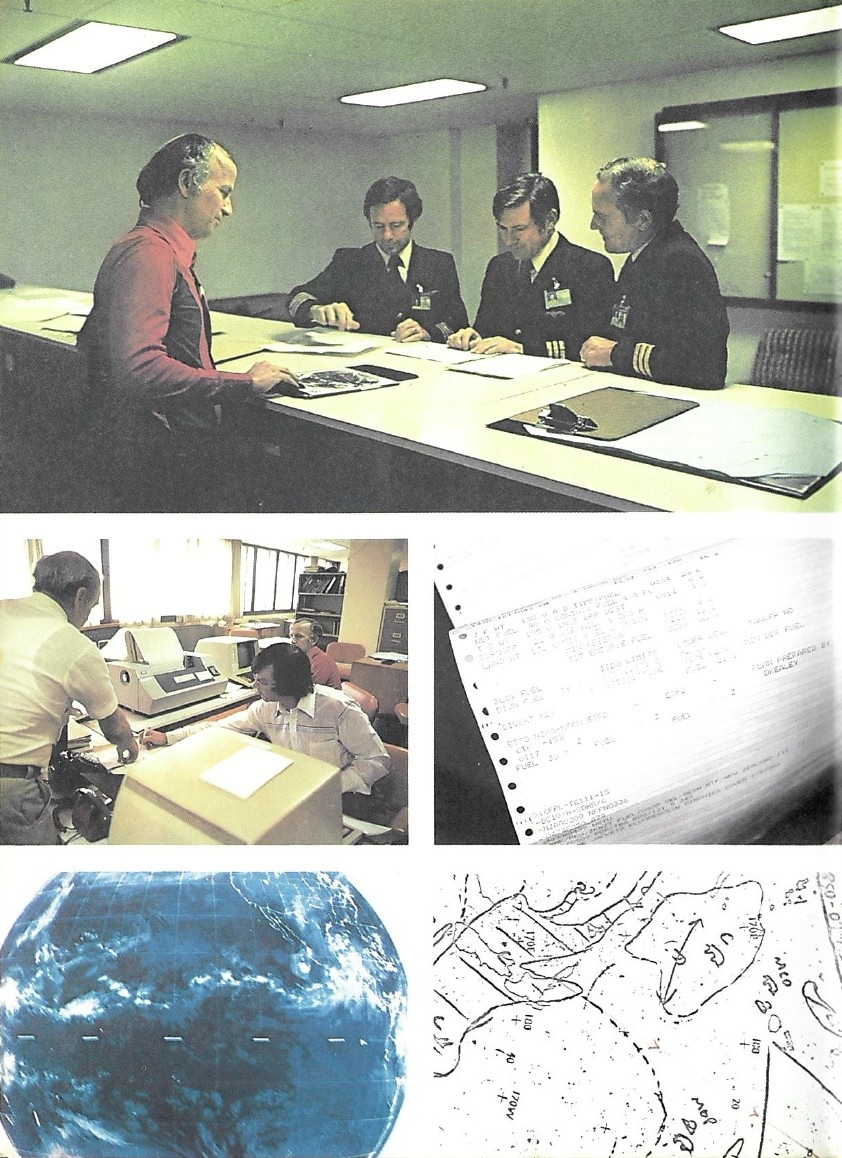

The three crew members assembled for the briefing. At the briefing they were given a flight plan and a met report. Met is short for meterological so a met report gives the crew an indication of the type of weather they can expect to find on their flight.

The flight plan had been prepared by a computer. A wide variety of information is fed into the computer which then calculates all the information necessary for the flight. It indicates the route to be flown, even showing an alternate port if weather conditions don’t allow the aircraft to land at its correct destination. It also gives information on the amount of fuel being carried and a calculation on the amount of fuel being used throughout the flight. This information, together with a pre-flight information bulletin and met reports is given to the flight crew. A Briefing Officer then discusses all this information with them.

These days, weather forecasting is helped greatly by photographs taken from weather satellites. One satellite, stationed high above the Pacific Ocean, shows the weather for the whole region. Other detailed charts give information on winds, air pressures and temperatures.

After briefing, the crew moved over to the aircraft. Loading of cargo, loading of in-flight facilities and final preparations for the flight were being done. The crew boarded the aircraft in preparation for the flight.

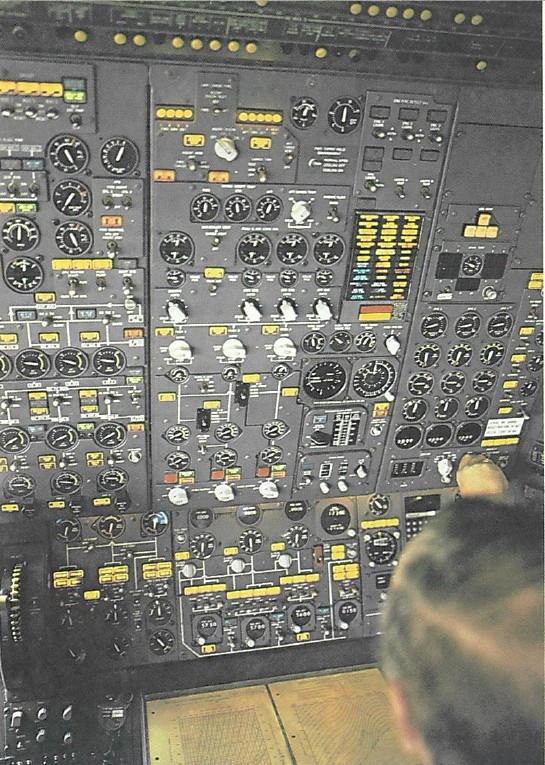

The whole crew then began a series of pre-flight checks. These checks are done in a special order to make sure nothing is overlooked.

The Flight Engineers has two tools that he takes with him while he’s doing these checks. His tools are his screwdriver and his torch. Remember that these tools are not used to fix, but just to test things. He uses his screwdriver to test for water in the fuel. This is how it’s done.

A sample of jet fuel is taken from each of the aircraft’s four tanks. These tanks are located in the wings. The fuel samples are placed in four glass jars. The Flight Engineer inspects each jar in turn. He dips his screwdriver into a special compound and then dips it into the jar. If the colour of the compound changes this indicates there is water in the fuel. If this was the case, more samples are taken until the engineer is satisfied there is no water left in the fuel.

These sample bottles are labelled and kept as a record of the test.

Finally, he checks to make sure that the doors to the cargo holds are properly closed. He carefully watches as one of the ground staff closes the doors and locks them. Once this is done the Flight Engineer returns to the flight deck. Everything is now in readiness for the aircraft to start its engines and move away from the airbridge.

As the tractor pushes the aircraft away from the airbridge, the flight deck crew began its second round of pre-flight checks.

The giant plane swung on to the end of the runway and final take-off clearance was received.

The Cabin Crew

It was happening all over again, but this time it was from Sydney to Auckland. The same flight crew that had brought the DC-10 to Sydney were now taking her home.

For every take-off and every landing, the procedure was the same. Checks and double checks are made in a routine way. Nothing is left to chance. That’s what makes flying the safest way to travel.

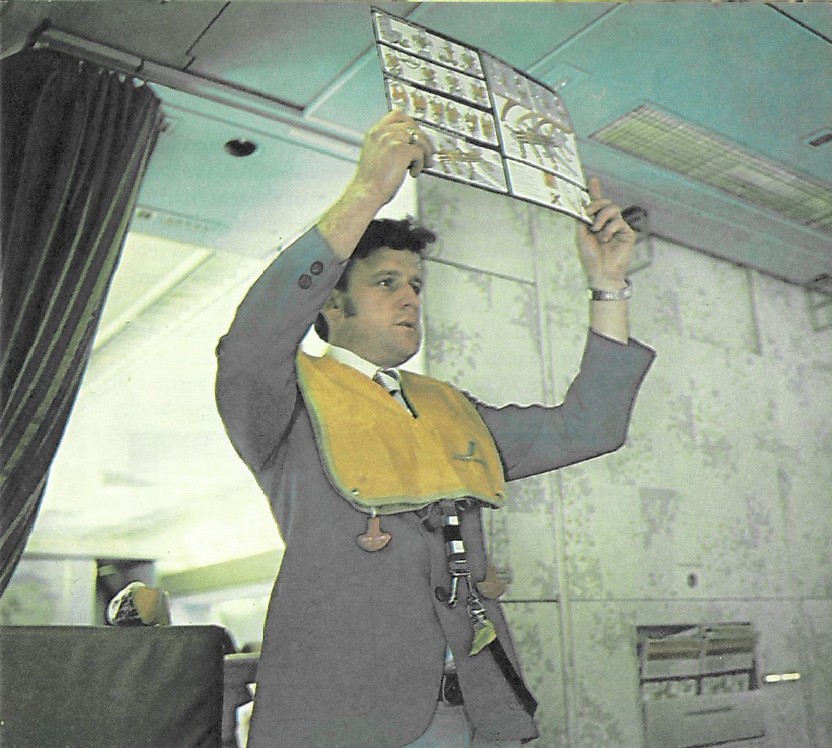

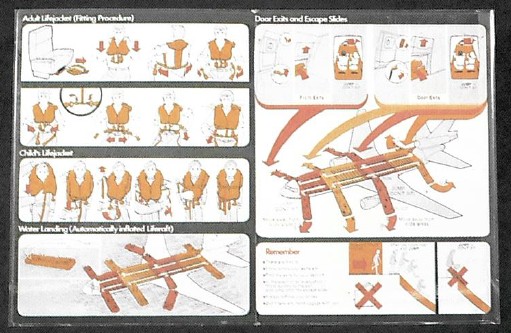

I was in my seat, with my seat belt on and the cabin crew had just begun the safety demonstration. We were all told to check the card in the pocket of the seat in front of us. This card explains details of the aircraft and what to do if there is any emergency. The cabin crew demonstrated the lifebelts, explained about special equipment for young children, and talked about the escape slides that are located at each door. Next, the oxygen masks were explained and attention drawn to the NO SMOKING, FASTEN SEAT BELTS sign.

Finally, he said that stereo headphones could be hired for $2.50 for the flight. This would give the listener a choice of ten programmes to listen to. He signed off, wishing us all a pleasant flight.

By this time the DC-10 had reached the end of the runway. Just before the engines began to rev up, the Flight Engineer announced, “We are awaiting our clearance. Would the cabin staff take their seats.”

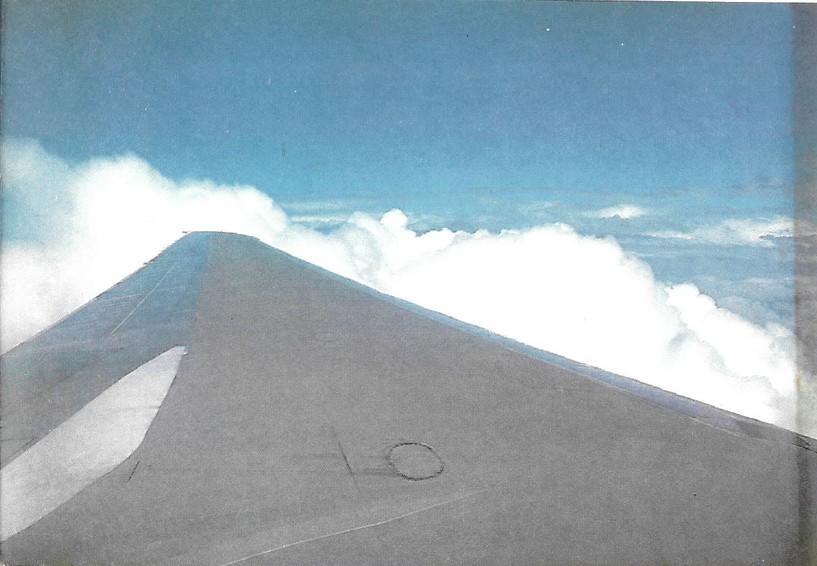

It was just nine minutes from the time we had been pushed away from the airbridge. The engines roared and we started to roll down the runway. As we rose into the air, the aircraft banked to the left. I could see out the window and noticed that the two parts of the wing which extended to make it broader, were still out. The front parts are called leading edge slats, and the larger back parts, the trailing edge flaps.

“I’d be very interested to see how all the food is prepared for in-flight service. Would it be possible for me to see the flight kitchen when I am in Auckland?” I asked.

The Purser gave me the name of the person to see in Auckland. I was just about to go and sit down when the Flight Engineer came off the flight deck. The Purser introduced me to him.

“We’re flying at 33 000 feet,” (just over 10 000 metres) he told me. “At this altitude we’re using between 7500 and 8000 kilograms of aviation fuel per hour. For the crossing we’ve got 43 000 kilograms of fuel on board, so you can see that there’s a big safety margin.”

We chatted for a while. He’d started working with Air New Zealand as an apprentice ground engineer. He’d done all his examinations until he’d qualified as a chief ground engineer. Then, he’d moved over to the flight crew and had been flying the DC-10s ever since the company had introduced them.

“I’d better get back to the flight deck,” he said. “The Captain will wonder where I’ve got to. If you like I’ll ask permission for you to come on to the flight deck. If he allows it, this will be a very special circumstance because you’re writing a book about flying. Will you just wait here for a minute?”

“The skipper says it’s O.K., even if it is a bit unusual.”

I thanked the Flight Engineer and stepped on to the flight deck. I was introduced to the Captain and First Officer and sat down in the jump seat. Every six months all pilots have to undergo a flight check. On these flights, a senior pilot, known as a check captain, goes on a flight to check that everything is done according to the flight procedures laid down for that aircraft. The pilot being tested must pass this test so that he can continue to fly. This is just another way that the airlines ensure the safety of their passengers.

By this time we were almost half way to Auckland. Everything was normal and the aircraft was exactly on course.

While I was on the flight deck I listened to the radio communications, even though I found them hard to understand. “The radio is something you get used to,” said the First Officer as he made some calculations on his pocket calculator. “We’re right on time, skipper. Our estimated time of arrival at Auckland will be 6.17 p.m. Auckland time. I’ll tell the passengers.”

“Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. This is the First Officer speaking. We’ll shortly be starting our descent into Auckland and expect to be on the ground at seventeen minutes past six local time. Auckland time is two hours ahead of Sydney so you should put your watches forward two hours.”

From up on the flight deck everything looked so calm. Big white fluffy clouds were below us while we were flying in bright sunlight. When I looked upwards, the sky looked black.

There was no sensation of speed although we were travelling at more than 1000 kilometres per hour.

I thanked the Captain and First Office. It had been very interesting talking to them. Both had joined Air New Zealand from the New Zealand Airforce where they had learned to fly. They both had families, whom they would drive home to when the flight touched down at Auckland.

“I do spend a lot of time away from home,” explained the Captain, “but only for a couple of weeks at a time. Because pilots are allowed to fly only a certain number of hours each month, I also have more time off than most other people. When I’m not flying I keep fit by doing plenty of exercise and being just a husband and dad. That means I do the things any other dad does – the lawns, the garden, watch TV, go to the movies, picnics, everything.

“But I love aeroplanes. I often read about modern aircraft not only as part of my job, but just for relaxation. Most pilots are like me; they just love to fly.”

I shook hands with the Flight Engineer and thanked him for taking me on to the flight deck.

“I’d love to see one of these aircraft in the workshop,” I said.

“I’m sure that can be arranged. I’ll have a talk with someone in the Company when we land. If you ring them tomorrow, they’ll tell you the arrangements. These aircraft are beautiful and fast in the air, but on the ground they look massive. Wait till you see one in the workshop.”

I left the flight deck and returned to my seat. I could feel that we had started our descent and would be landing shortly. What a wonderful flight I’d had to Auckland. And what thrilling things were being arranged for me to see.

In the Workshop

Early next morning I arrived at the workshops with an employee of the company. We needed special permission to enter all these parts of the airport but this had already been arranged.

First we walked through the spare parts store. If you think your local garage carries a lot of spare parts, you should have seen this. There wasn’t one thing you couldn’t have found here. There were wheels and tyres and engines and covers. On and on and on they went.

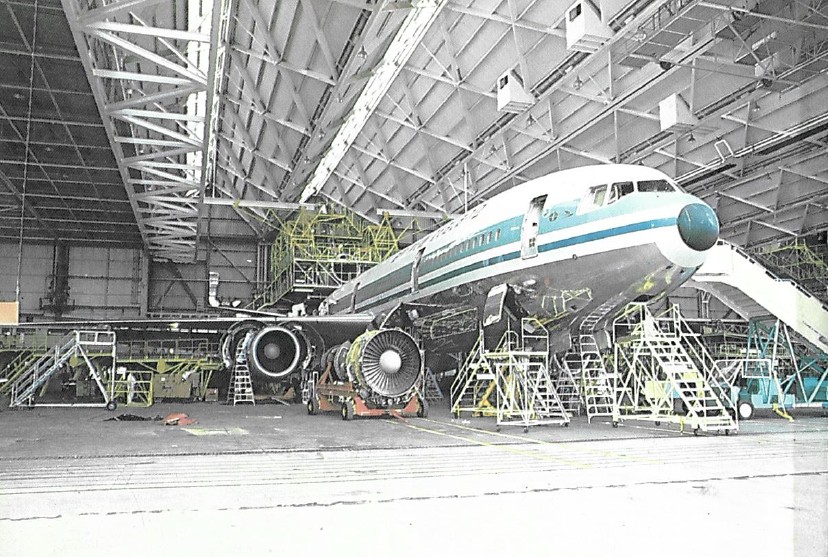

“When we pass through this door, we’ll be in the hangar,” said my guide. “We’re very lucky because there’s a DC-10 being serviced. They don’t spend much time in here, you know. Work goes on twenty-four hours a day.”

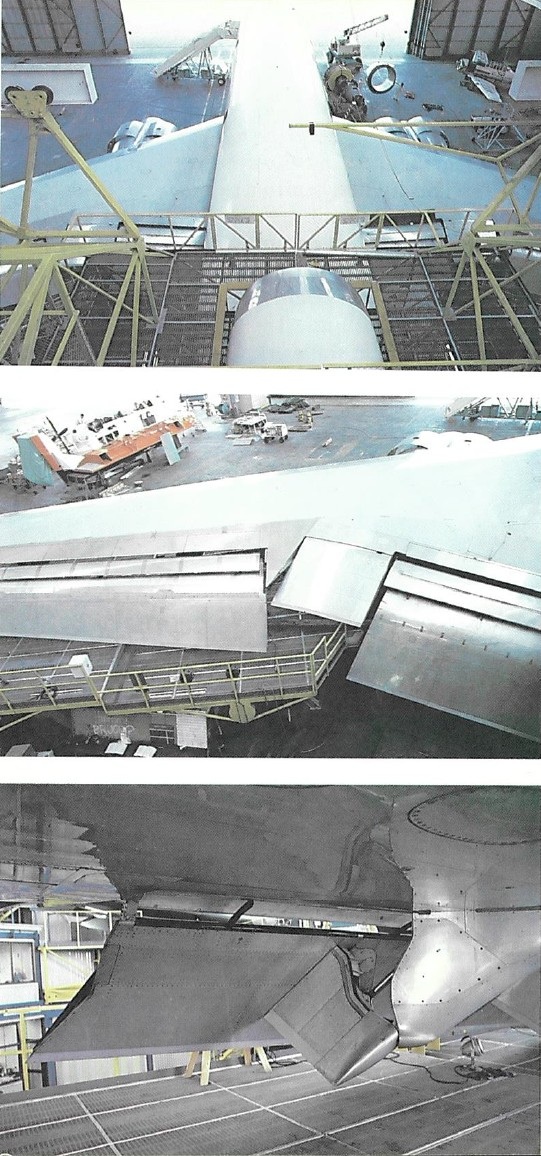

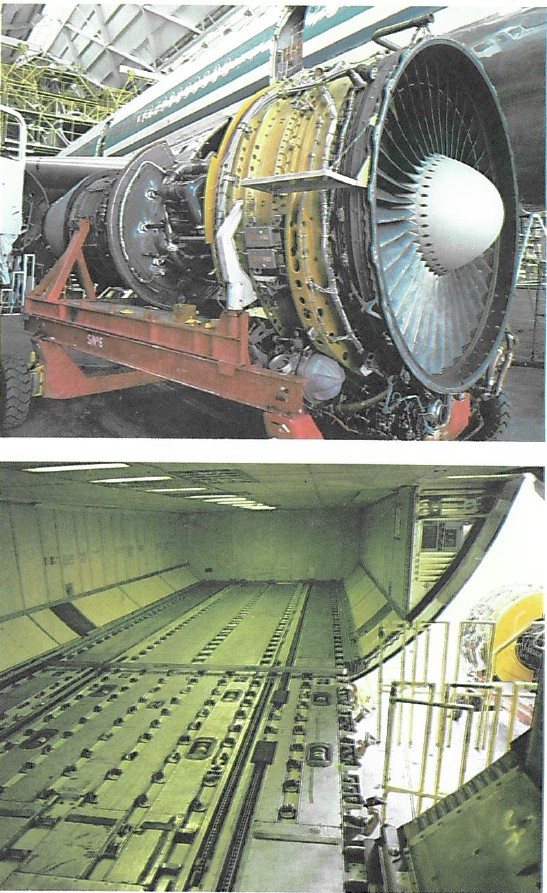

We opened the door to the hangar and there was the DC-10 surrounded by scaffolding, platforms and ladders. The highest scaffold went right to the roof of the hangar. This was the scaffold and platform used to service the tail section and the rear motor.

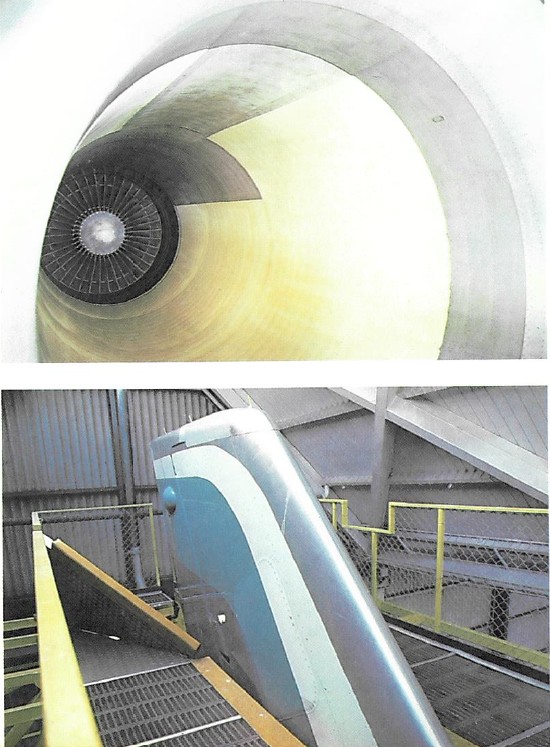

We climbed up this scaffolding until we came to the air intake of the rear engine. But the top of the tail was even higher, so we climbed up there. From this position we looked down at the work going on below us.

“Let’s go and have a closer look at the engine,” I said.

We came down from our elevated platform, walked under the wings and over to the engine. Several engineers were working on the engine still in the DC-10.

We moved away from the engineers working on replacing the engine, and climbed some steps up into the cargo hold. The DC-10 has two cargo holds, which are underneath the passenger deck.

Inside the aircraft, all the interior was being thoroughly cleaned and checked. Everything looked in a state of disarray but I knew that by the following night things would be back in their proper place and the aircraft ready to fly.

Two things became very obvious to me. Modern aircraft are very complex pieces of machinery which take many expert tradesmen to maintain. Secondly, although they are complex, major overhauls and services are done in a very short time. I kept thinking of how I have to leave my car for a full day at the garage for it to be serviced, but this complex aircraft can have a more thorough overhaul and it doesn’t take very much longer.

I looked at my watch and was amazed that we’d spent so much time here. I suppose the time had just seemed to disappear because there were so many new and interesting things to see.

The Flight Kitchen

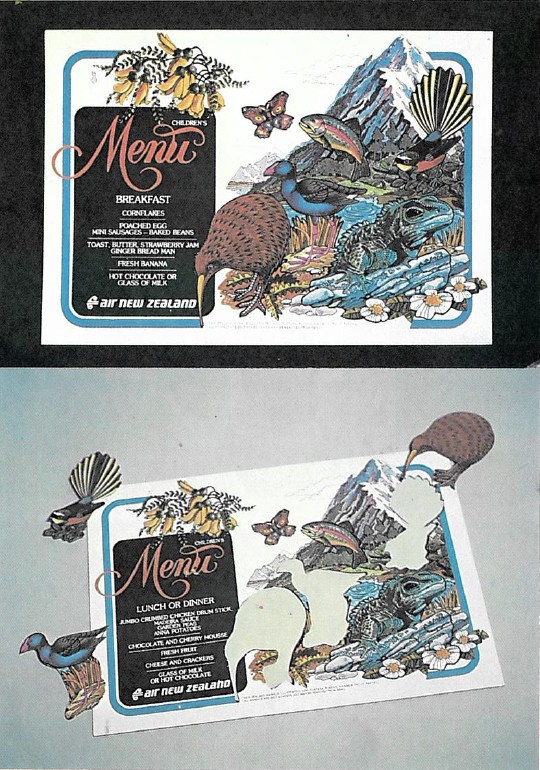

A tour of the flight kitchen had been arranged for the next morning. We would be looking at how the food was prepared, how it was stored, how it was put on board the aircraft, and finally what happened about the “washing up” after a flight.

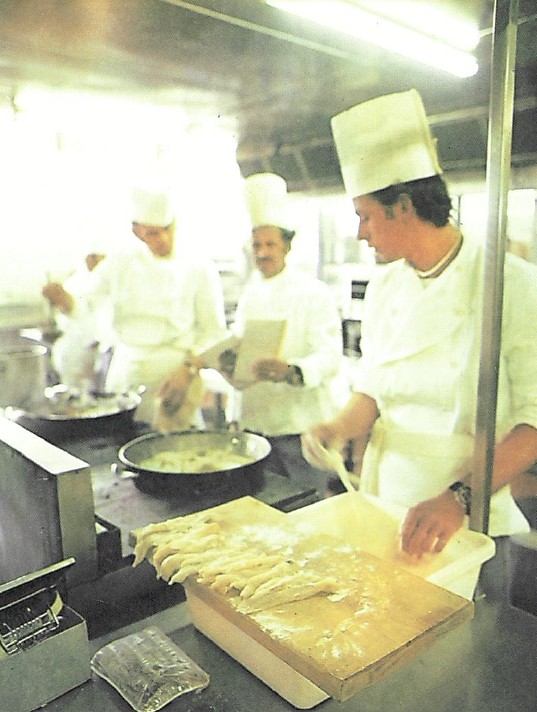

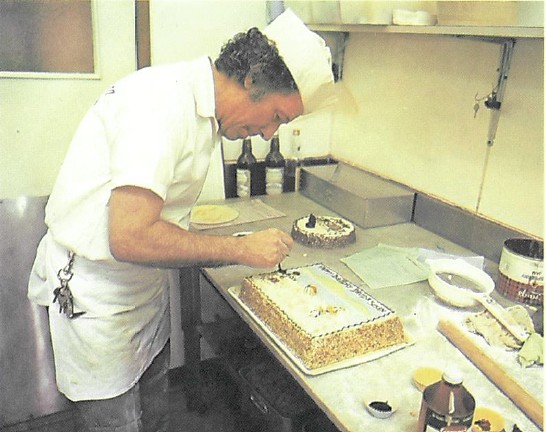

“We’ll look at the meal preparation first,” said my guide. “This section is under control of a master chef who has eighty-nine cooks and kitchen hands as well as ten apprentice cooks working for him.”

I was introduced to the chef who took me on a tour of the kitchen.

“This is where we start,” he said. “We receive a photograph of the meal precisely as the airline wants it served. We prepare the meal to look exactly the same as the photograph. If you look at the board you’ll see not only the Air New Zealand meals, but meals that we’re preparing for other airlines as well. You can see PAA (Pan American), QEA (Qantas), and the French airline UTA. We’re just waiting on the order from British Airways.

“When you look around you will see food being prepared, cooked and dished out.”

“Who’s the birthday cake for?” I asked.

“And that marvellous bread smell?” I asked.

“Yes, we bake our own bread and rolls. It does smell nice, doesn’t it?

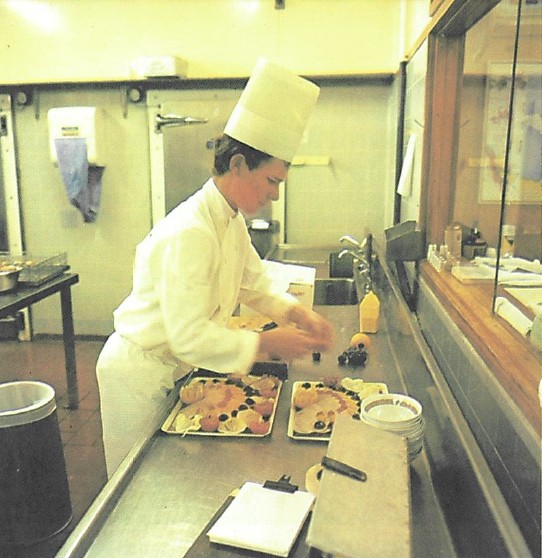

“The last part to see is the meals being dished up. Ah, they’re dishing up lunch for the Auckland-Sydney flight tomorrow morning.”

Hundreds of dishes were lined up on a long metal table. Two cooks were putting the final touches to tomorrow’s lunch.

“What happens from here?” I asked.

“The food is placed in cabinets which are stored in a large refrigerated room in another part of the building.

I thanked the chef and walked over to where the food was stored. Here I was met by the catering supervisor.

“We prepare the trays here,” her said, “and load them into cabinets. These cabinets are also stored in refrigerated rooms until they are taken to the aircraft. Here are some trays being prepared.”

“Next door we have our store. We’re replacing things all the time, so we have to make sure we have stocks of everything.”

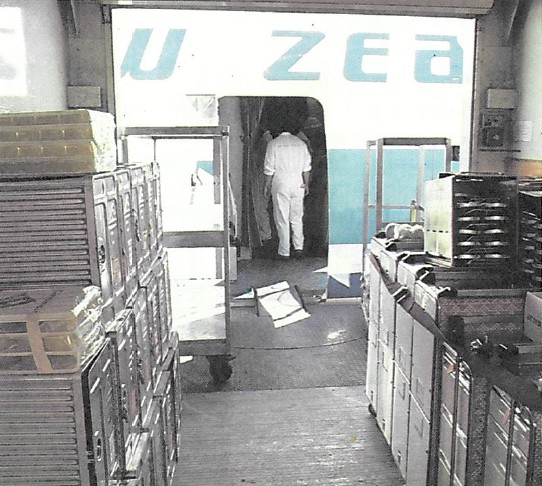

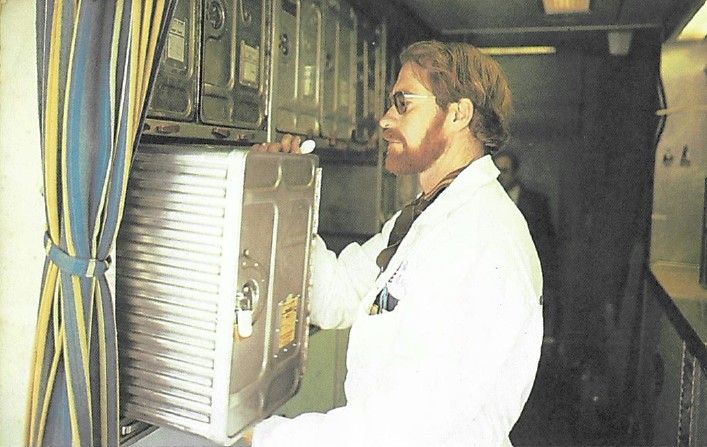

After walking through the gigantic stores we saw food being loaded on to a truck. We had seen these trucks pull up beside the DC-10 and the back raised until it was level with the galley door of the aircraft. The food boxes and cabinets are then transferred from the truck into the galley, where they are used during the flight.

“It’s like everything else that’s involved in running an airline,” he said. “Everything is thought out to the last detail and always checked. And, like the DC-10s, it’s big and complex.”

“I can certainly see that,” I said and thanked him for the opportunity of seeing this very important part of the operation.

“Did you know we run a school here?” asked my guide.

“A school? What do you mean?”

“I mean a real school; with real students, real classrooms and real teachers. Of course it’s not a school for children but a school to teach stewards and hostesses how to do their work. They’re having classes now, but we can peep in at one of their special classrooms.”

He took me to two classrooms that looks just like the inside of an aircraft.

“This is where they practice what to do before they have their first flight. You can see it looks just like an aeroplane.”

Air Traffic Control

“The company seems to have thought of everything,” I said. “But there’s one more thing I’d like to know more about, and to do that we’ll need to visit the control tower. I’d really like to see what it’s like to be an air traffic controller.”

“Well, that’s not run by Air New Zealand. Air traffic control is run by the government. We’ll need special permission to go up into the tower but I think we can get that. Why don’t we leave that until tomorrow.”

“Well, tomorrow’s my last day,” I said. “I leave on Friday and I’m sure there are still a few things to catch up on.”

“There probably are, but we’ll catch up on those tomorrow.”

From the control room we had an excellent view of the whole airport; the terminals, the taxiways and the main runways.

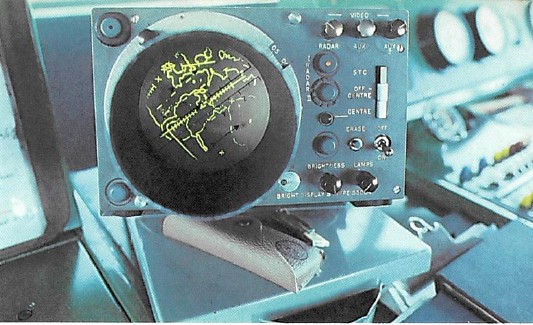

After we arrived, a controller was speaking by radio to the pilot of a light aircraft that was in the area. The position of the aircraft was shown on the radar screen, although it wasn’t visible from the tower.

“There’s not much traffic around at present,” he said, “but we have times when it’s very hectic.”

He explained that the controller on duty was responsible for directing the traffic into and out of the controlled area. There were certain safety standards that had to be observed always, to make sure aircraft did not get too close to each other.

“You’re a bit like a policeman directing traffic,” I said.

“Not exactly. Motor traffic certainly goes in different directions at different speeds at the same time, but they’re all on the same level. We have them all going at different directions at different speeds and also travelling at different heights, which change all the time.”

“Not so easy,” I agreed. “I’m glad it’s your job and not mine. It’s like everything else I’ve found out about flying and aircraft. It’s a very complicated business.”

We would have chatted more but a light aircraft was in the area and was reporting to the tower. We left, greatly respecting the work of all those in the control tower.

Back on the Ground

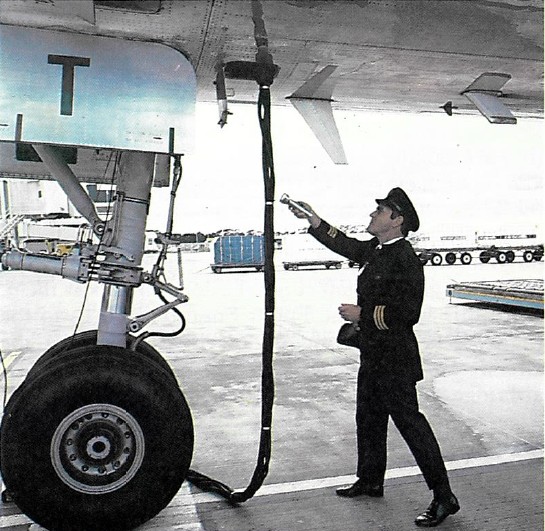

“There’s a flight going off at four o’clock this afternoon,” said my guide. “If we hurry across we can watch the final refuelling and any last minute preparations being made.”

We arrived and walked on to the tarmac beneath the giant DC-10. The refuelling truck was already there with the giant hose screwed into one of the aircraft’s fuel tanks. The other end of the hose ran across the tarmac to the underground fuel tank.

I’d learned so much about the complex way airlines work. When I fasten my seat belt for my flight tomorrow, I’ll be aware of what’s happening on the flight deck and how much preparation has gone into making me relaxed and comfortable. And I’ll keep in my mind the way the engineers have looked after this aircraft when it went in for service. I’ll know as I hear the roar of those mighty engines, that this aircraft has been cleared for takeoff by an air traffic controller who even then will watch as my giant bird rolls faster and faster down the runway.

Overall Thoughts

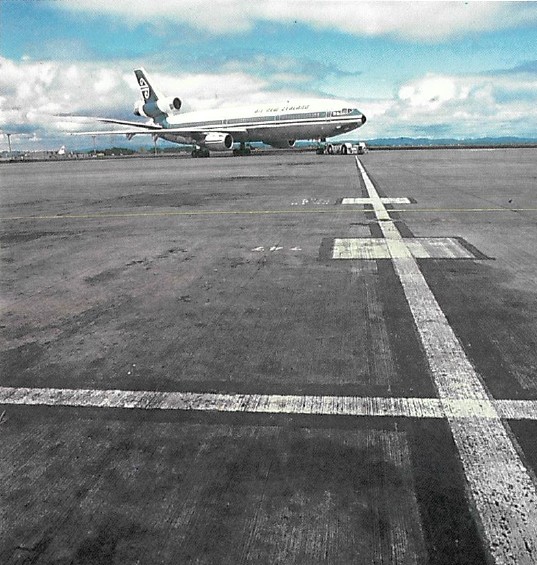

Well, there you have it. Flight 605 is a real snapshot of the Air New Zealand operation in 1980. What is remarkable is that not much has changed at all. Apart from the fact there is individual entertainment on board and flat seats in business class, aviation has changed very little from a passenger perspective. Even though tech has also improved behind the scenes, a lot of what is above is similar to today.

I wonder if anyone who flew for Air New Zealand back then recognises any of the people in the pictures. As an aside, I wish I had the original pictures to make proper scans, as the scans don’t really do the images justice. They’re so good for the book though, it was very impressive to me as a boy. Still is, really!

What do you think of Flight 605? Did you ever travel on a DC-10 or on Air New Zealand back then? Thank you for reading and if you have any comments or questions, please leave them below.

Like planes? See my “Does anyone remember” series.

Flight reviews your thing? Mine are all indexed here.

Follow me on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Flew with Air NZ a d years later married my late hubby Captain Earle Garratt. Loved his tales of many flights etc. Flying g was his passion until he retired around 1988/89.

Oh that’s lovely, the company will be in your DNA at this point. Thanks so much for the comment and hope you enjoyed the read!

My first and second trips to New Zealand were aboard DC-10s. I flew on of TE’s in 1981, just before the type was replaced by 747s on the LAX-NAN-AKL service, then my second trip, in 1983, was aboard a CO DC-10, LAX-HNL-AKL. My subsequent trips were all on 747s, both via TE (later NZ) and QF.

That’s pretty cool. I flew on the DC-10 twice, both with United back in 1991. One was a DC-10-10 and the other a DC-10-30. Glad to have flown on them – just those two times though. Great you flew with Air New Zealand!